Advertisement

When

Ghana

discovered

oil

in

2007,

some

observers

predicted

the

“Dutch

Disease”

as

the

variant

of

the

resource

curse

awaiting

the

country.

In

new

research

by

Colin

Constantine

of

Cambridge

and

Tarron

Khemraj

of

NCF,

it

is

shown

that

the

classical

Dutch

Disease

has

not

manifested

in

Ghana

after

nearly

15

years

of

oil

production.

(Simplifying

massively

hereon.)

The

classical

Dutch

Disease

proceeds

as

follows

-

Country

discovers

oil

(or

other

major

tradable

natural

resource); -

A

sudden

surge

of

exports

generates

massive

forex

inflows; -

The

country’s

currency

strengthens; -

Imports

become

cheaper,

undermining

some

local

industries; -

There

is

a

shift

of

resources

and

emphasis

to

the

new

oil

sector;

and -

Legacy

industries

suffer

and

the

economy

comes

under

pressure.

Constantine

and

Khemraj

provide

evidence

in

their

new

preprint

(link

to

full

paper

in

first

comment)

that

this

sequence

doesn’t

apply

in

the

case

of

Ghana.

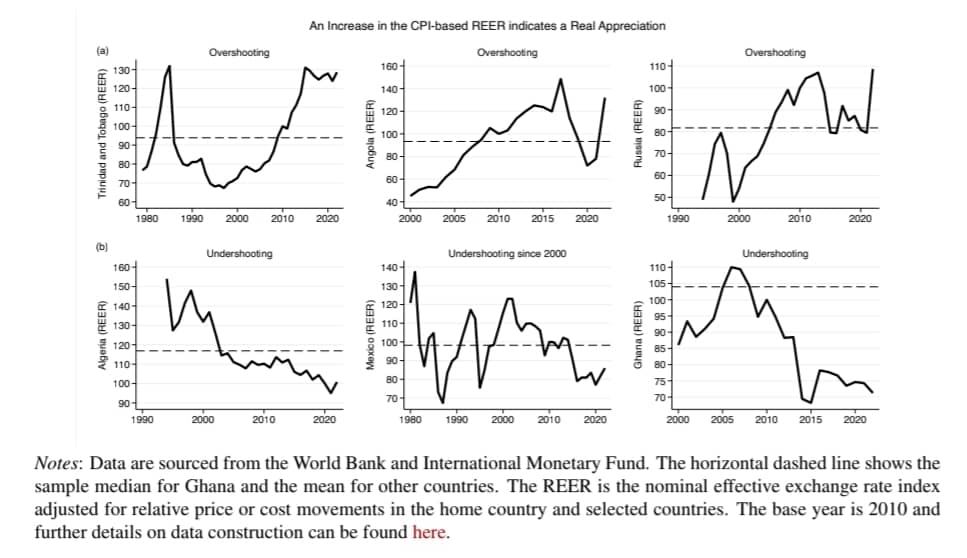

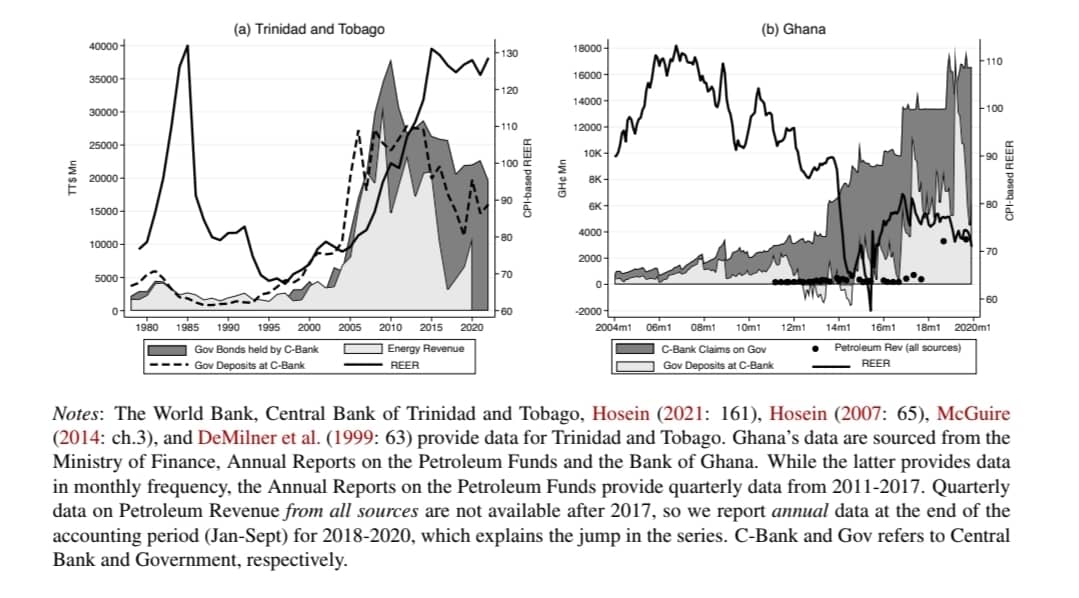

It

does

fit

the

case

of

Angola

though.

As

well

as

Trinidad

and

Tobago’s.

At

any

rate,

in

a

liberal

economic

setting

where

imports

can

flow

without

too

much

friction,

a

surge

in

forex

inflows

from

resource

exports

should

ordinarily

not

trigger

the

first

step

in

the

sequence:

over-valuation

of

the

currency.

In

Ghana’s

case

(as

also

in

Algeria

and

Mexico),

new

oil

finds

have

coincided

with

exchange

rate

depreciation.

Ghana’s

situation

in

particular

is

pretty

alarming.

Since

it

became

an

oil

producer

in

2007,

Ghana’s

currency

has

fallen

by

over

93%

in

value.

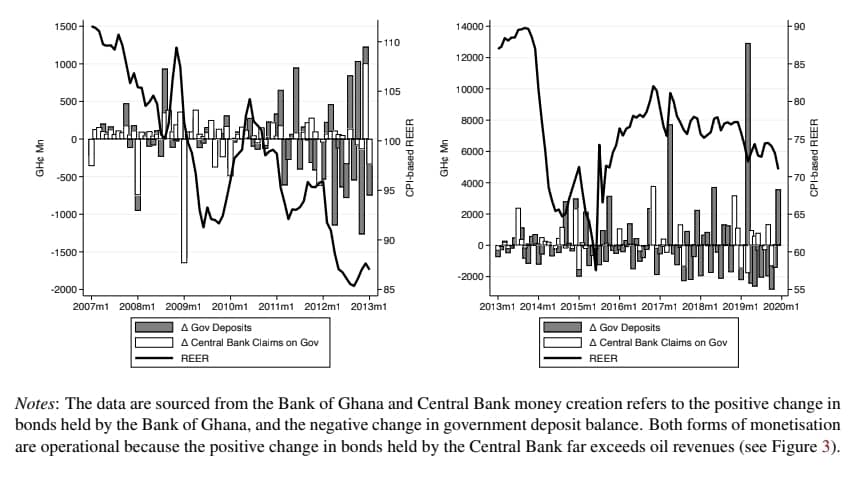

The

Constantine

&

Khemraj

paper

spotlights

one

important

cause

of

the

Cedi’s

precipitous

decline:

the

role

of

the

Central

Bank

in

the

“monetisation”

of

the

fiscal

deficit.

Fiscal

deficit

monetisation

came

up

in

the

discussions

during

2022

when

the

Ghanaian

currency

lost

more

than

50%

of

its

value

in

less

than

a

year.

However,

this

paper

is

one

of

the

few

empirical

investigations

into

the

interconnected

variables

at

the

root

of

the

phenomenon,

even

if

its

focus

was

not

on

the

acute

factors

that

precipitated

Ghana’s

debt

default

and

is

instead

on

the

long-term

currency

movements

linked

to

the

fiscal

and

current

accounts.

Whilst

the

paper

does

require

a

careful

analysis

of

the

relations

among

such

important

macroeconomic

indicators

as

bank

credit,

government

deposits,

and

resource

rents,

the

emphasis

on

central

bank

behavior

will

find

perfect

resonance

with

the

mood

of

analysts

and

activists

in

Ghana

who

have

been

sceptical

of

the

policy

conduct

of

the

Bank

of

Ghana.

My

personal

view

is

that

the

scale

and

maturity

of

the

oil

industry

in

case

study

countries

could

also

have

an

interesting

role

to

play

in

whether

monetary

outcomes

result

in

distortive

appreciation

or

depreciation

of

the

currency

in

the

wake

of

oil

finds.

Still,

any

rigorous

work

that

shines

much

needed

light

on

the

central

bank’s

role

in

these

turbulent

fiscal

times

is

a

vital

contribution

to

the

conversation.

By – Bright

Simons, Vice-President,

IMANI